/ 6 min read

Applying Knowledge Graphs to Digital Social Care

Introduction: The Semantic Gap in Social Care

Across the UK, adult social care data lives in a patchwork of systems, spreadsheets, and bespoke databases.

Each local authority, care provider, partner agencies and care provider collects information differently - with its own schema, naming conventions, and business logic. One organisation records “care package start date,” another calls it “service commencement,” and a third stores it as free text in a word document.

The result? Endless manual reconciliation, costly integration projects, and a loss of context between what happened, to whom, and why.

To move toward true interoperability, we need more than shared APIs - we need shared meaning.

From Data Aggregation to Data Understanding

Most social care data initiatives focus on aggregation: combining data from multiple sources into a warehouse or dashboard. But aggregation doesn’t equal understanding.

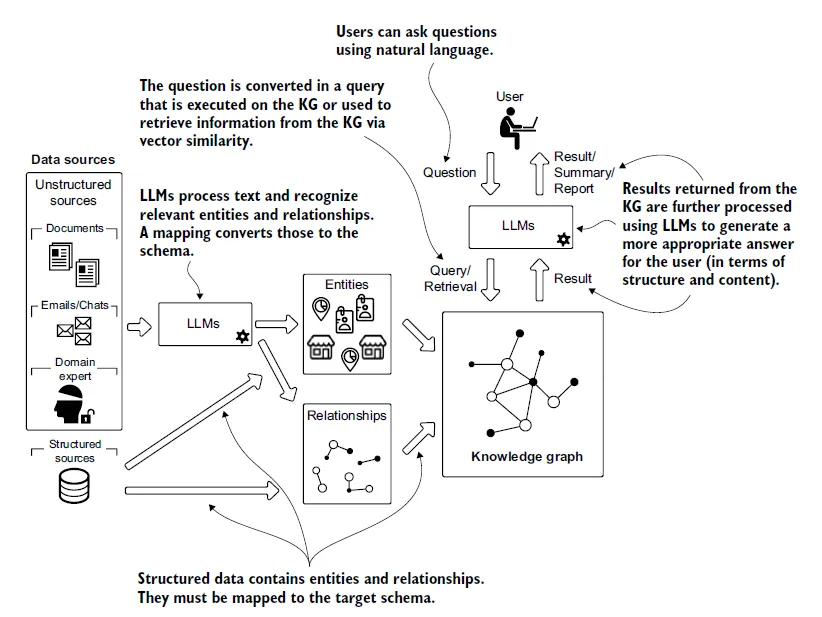

When you bring together data that describe the same reality in different ways, you risk distorting the truth rather than clarifying it. Alessandro Negro, in Knowledge Graphs and LLMs in Action, argues that Knowledge Graphs serve as a bridge between data and meaning - allowing information from disparate systems to coexist and interconnect semantically.

That same principle applies here. The challenge in adult social care is data semantics and interoperability.

Knowledge Graphs and LLMs in Action - Alessandro Negro, Manning Publications

MODS and Contsys: A Foundation for Meaning

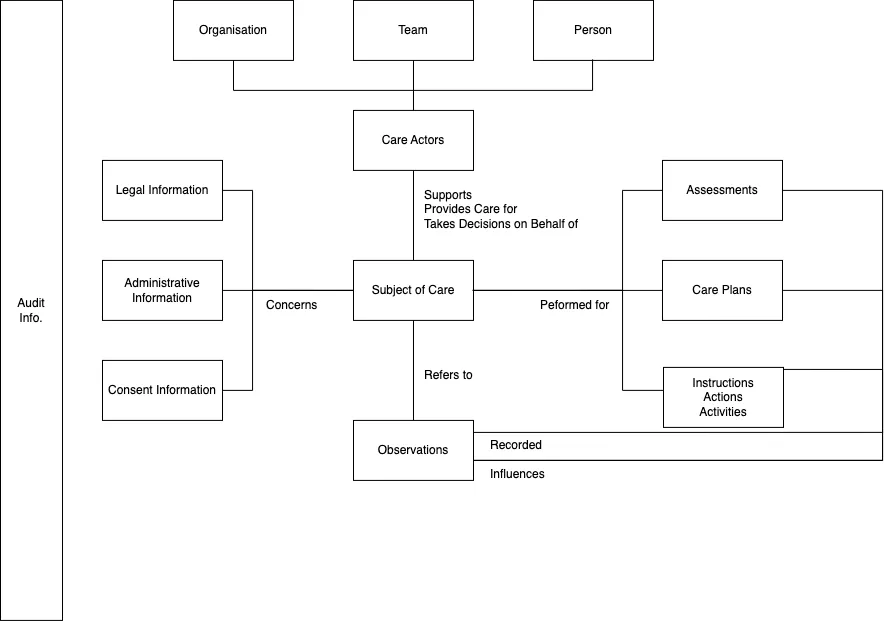

The MODS Conceptual Data Model (Minimum Operational Data Set) offers a shared semantic foundation for social care.

Built on the international standard EN ISO 13940:2016 (Contsys:2019) - which defines the Continuity of Care model - MODS provides a common conceptual vocabulary for describing people, interventions, needs, assessments, and outcomes.

In practice, MODS translates between the local dialects of social care information systems and care providers.

A “service user” in one dataset can align with a Person in MODS; “assessment outcome” can map to a Goal; “reablement plan” can link to an Intervention.

The ontology gives these concepts relationships and formal meaning, ensuring that when data moves between systems, its intent is preserved.

Knowledge Graphs: The Missing Semantic Layer

Knowledge Graphs provide the architecture to connect these semantics in action.

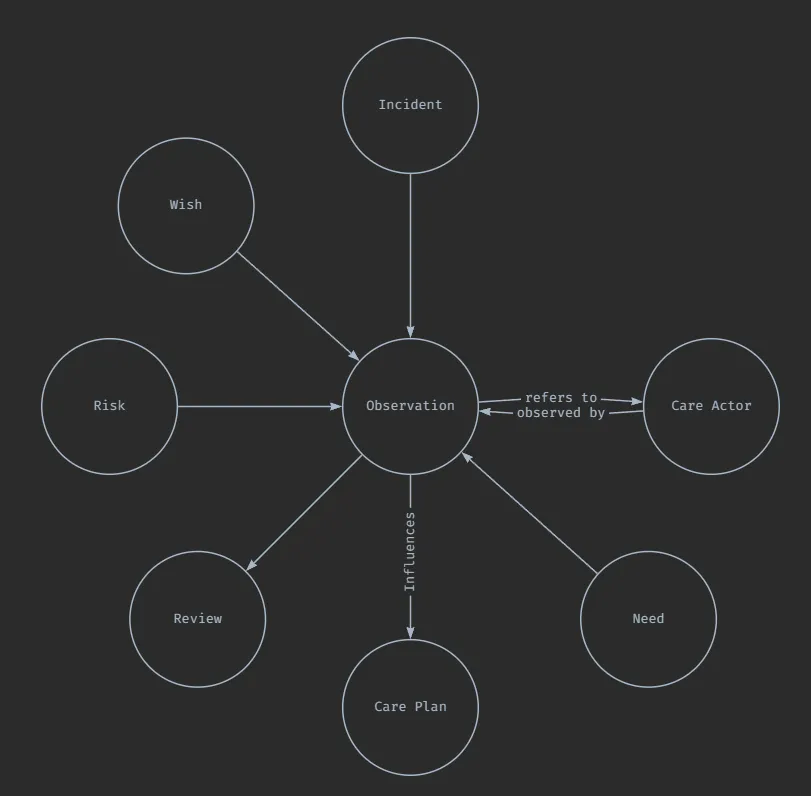

Unlike traditional databases that store isolated rows and columns, Knowledge Graphs represent entities and their relationships - who, what, and how - in a unified graph model.

This makes them ideal for social care, where understanding context is essential: a Person receives Services delivered by a Provider as part of a Care Plan derived from an Assessment.

When powered by an ontology like MODS, a Knowledge Graph can unify CSV exports, case management data, and provider systems into a single, semantically rich layer.

It becomes possible to ask questions like:

- Which individuals have open assessments with no linked outcomes?

- How many interventions address similar goals across different providers?

- Where are gaps emerging between needs identified and services delivered?

Strategic Outcomes for Digital Social Care

Adopting MODS and Knowledge Graph principles offers more than technical neatness - it creates tangible, systemic benefits:

- Interoperability by design – Data shared between systems carries meaning, not just structure.

- Context-aware analytics – Understanding the why behind metrics, not just the what.

- Safer data reuse – Shared definitions reduce misinterpretation of sensitive care information.

- AI-ready infrastructure – Ontology-grounded data enables reasoning, entity linking, and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) for large language models.

This semantic layer turns fragmented records into a connected narrative of care.

From Concept to Implementation

In the next post, I’ll move from theory to practice - building a Proof of Concept Knowledge Graph that uses MODS as its reference ontology.

I’ll walk through the pipeline step-by-step: ingesting example datasets, mapping them to MODS, loading them into a graph store, and exploring queries that reveal new insights.

A useful framework for structuring this process is CRISP-DM (Cross-Industry Standard Process for Data Mining). Originally developed for analytics and data science, its cyclical approach - from business understanding and data preparation through to modeling, evaluation, and deployment - aligns neatly with the iterative nature of Knowledge Graph construction. Each step of CRISP-DM can be mapped to a graph-based workflow: understanding the care context, defining semantic mappings, integrating and transforming data, evaluating relationships, and finally operationalising insights. It provides a pragmatic methodology for turning conceptual ontologies like MODS into operational knowledge systems.

Conclusion

Knowledge Graphs represent a fundamental shift in how we structure and reason about information. They bring a structured representation of human knowledge into machines, enabling more intelligent and context-aware behavior. In a Knowledge Graph, entities such as people, organisations, services, or clinical conditions are represented as nodes; their relationships - who did what, when, and why - form the connecting edges; and properties such as dates, types, and classifications provide essential context.

This explicit representation allows machines to reason about care information rather than merely store it. For social care, it means the system can understand that a Person is linked to an Assessment, that the Assessment leads to an Outcome, and that the Outcome relates to an Intervention delivered by a Provider. That relational structure turns raw data into knowledge that can support decision-making and predictive analytics.

However, despite their power, Knowledge Graphs have not been widely adopted. They are expensive to build and maintain, requiring careful schema design, ontology mapping, and ongoing data stewardship. Querying them efficiently also demands different access patterns than traditional databases - information is distributed across multiple nodes and relationships rather than flattened into rows and columns. And while structured data (like CSV or JSON) can be mapped predictably into a graph schema, unstructured data - free text in care records, assessments, or case notes - presents a far greater challenge. Extracting meaningful entities from natural language requires algorithms that can handle typos, ambiguous pronouns, and the nuances of human writing across multiple styles and vocabularies.

This is where the future becomes exciting. As large language models and ontology-driven systems begin to converge, new platforms such as Cognee.ai are emerging to simplify the process - combining semantic data modeling with AI-assisted entity extraction and graph construction. Such tools could dramatically reduce the complexity of building and maintaining Knowledge Graphs, making them accessible to sectors like digital social care that have historically lacked the resources to invest in bespoke graph engineering.

The future of digital social care will be built not only on shared data but on shared understanding. By combining the industry concepts like MODS with the adaptive intelligence of Knowledge Graphs, we can create systems that don’t just record information - they understand it. And when data becomes understandable, it becomes actionable - a foundation for safer, smarter, and more person-centred care.